by Rabbi Jonathan Wittenberg

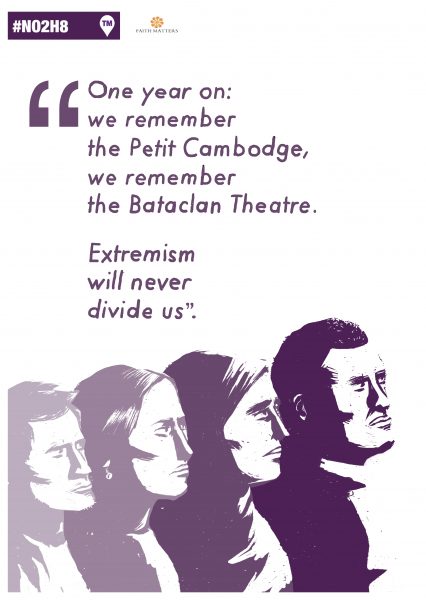

Today marks the first anniversary of the multiple attacks by Isil in Paris in which 130 people were murdered, 89 of them at the Bataclan theatre.

The beautiful building opened in 1865 and became famous as a home for music and entertainment. From the 1970s it became an important venue for rock, comedy and café-theatre. Those who attended the concert on Friday 13 November last year went to celebrate life.

I remember looking at the pictures printed in affectionate memory to honour the lives of those who were murdered there that night. They were mostly young, and happy. For those of us in our forties and fifties, they could have been our children on a night out. They had gone to enjoy life, when slaughter stole it from them.

When the three gunmen began to fire, people were mown down ‘like a gust of wind through wheat’. Many were shot as they tried to flee; others pretended to be dead. With supreme cynicism, the gunmen went round kicking bodies; if any moved, they were killed instantly.

On the eve of the anniversary the theatre has re-opened with a concert by Sting to ‘remember and honour those who lost their lives in the attack and to celebrate the life and the music that this historic theatre represents”. The opening song Fragile contains the words: ‘Nothing comes from violence and nothing will’.

Among those who attended were courageous survivors of last year’s atrocity, some in tribute to loved ones they had lost. Kelly Le Guen, who survived by barricading herself inside a room with twenty-five others said that she couldn’t wait ‘to see life and joy fill the room and not just carnage. Music and culture must re-stake their claim.”

The message on this anniversary must be that terror will never defeat the tenacity and bravery of the human spirit or destroy the profound love which binds human hearts together. It will not transform innocence and goodness into its own likeness.

Antoine Leiris lost his wife on that appalling night. Days later he posted on facebook a remarkable letter to her killers and those who supported them:

On Friday night, you stole the life of an exceptional being, the love of my life, the mother of my son, but you will not have my hate.

His words are a profound and inspiring expression of devotion and defiance. He subsequently published a book with the same title: You will not have my hate. Among the responses he subsequently received was one which read simply: ‘I want to respond to blind hate with blind love.’ It is reminiscent of the Talmudic idea that the only way to defeat causeless hatred is through love beyond all cause.

Both the Quran and the second-century rabbinic text the Mishnah contain the teaching that ‘One who saves a single life is as if they had saved an entire world’, while, conversely, ‘one who destroys a single life is as if they had destroyed an entire world’.

Every life is sacred, the unique embodiment of God’s spirit. Every life is a distinctive unfolding of the divine and has a distinctive capacity for creativity and compassion. No life is simply replaceable. Therefore murder is always sacrilege, never sanctification.

We have a choice: to be healers, or haters. Terror teaches us to work together, across all faiths and nationalities, not only to be vigilant but, more deeply, to help each other to be healers through compassion, understanding and love beyond all cause.