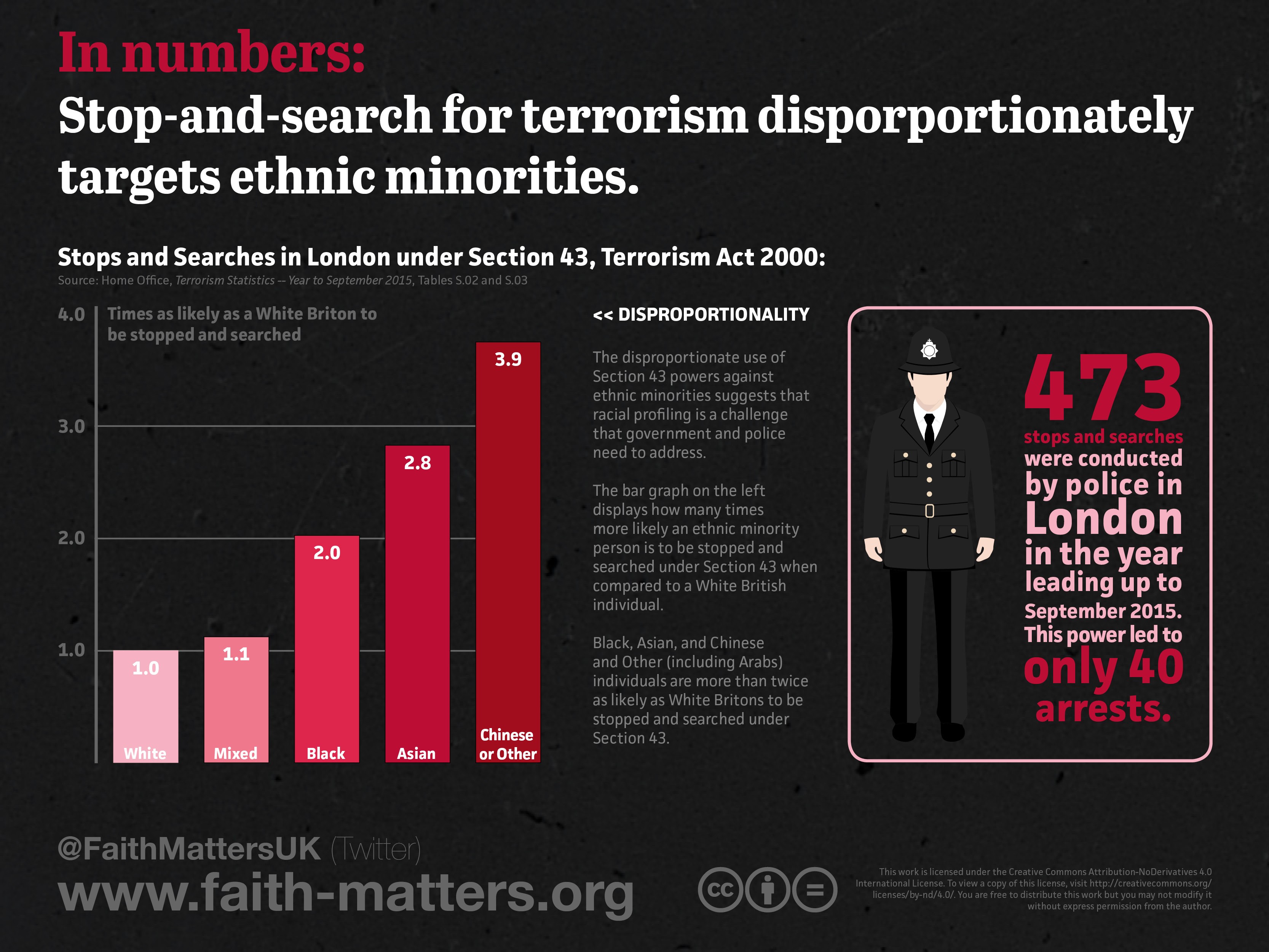

In September 2015, the Home Office released data on terrorism statistics, allowing us to review the use of terrorism-related powers on ethnic and religious minority communities. What we have found is that there is a significant level of racial profiling across counter-terrorism powers in Britain. All minority ethnic communities are affected by disproportionality but we see that people belonging to the category ‘Asian’ and ‘Chinese and Other’—which includes Arabs—are the most likely to be affected by terrorism powers.

Panel 1

We found that stops and searches in London under Section 43 of the Terrorism Act 2000 are more than twice as likely to be used on Black, Asian, and Chinese and Other people than White individuals.

Methodology

We have calculated this using the same methodology as the Equalities and Human Rights Commission’s (EHRC) report, Stop and Think. First, we take the proportion of each ethnic group to the total number of arrests. Then we compare that proportion with the proportion of that ethnic group in the population in London (available from the Office of National Statistics). We then compare the ratio of individuals stopped and searched by ethnic group as a proportion of the total number of stops and searches with the ratio of each ethnic group as a proportion of London’s total population. Finally, the product of this comparison is measured against the ratio calculated for White individuals, providing us with a number that tells us how many times more likely a person from a given ethnicity is to be stopped and searched by the police. This operation would also tell us if a member of an ethnic minority group is less likely to be stopped than a White person, but it appears that in almost all cases, ethnic minorities are more likely to be stopped and searched.

Panel 2

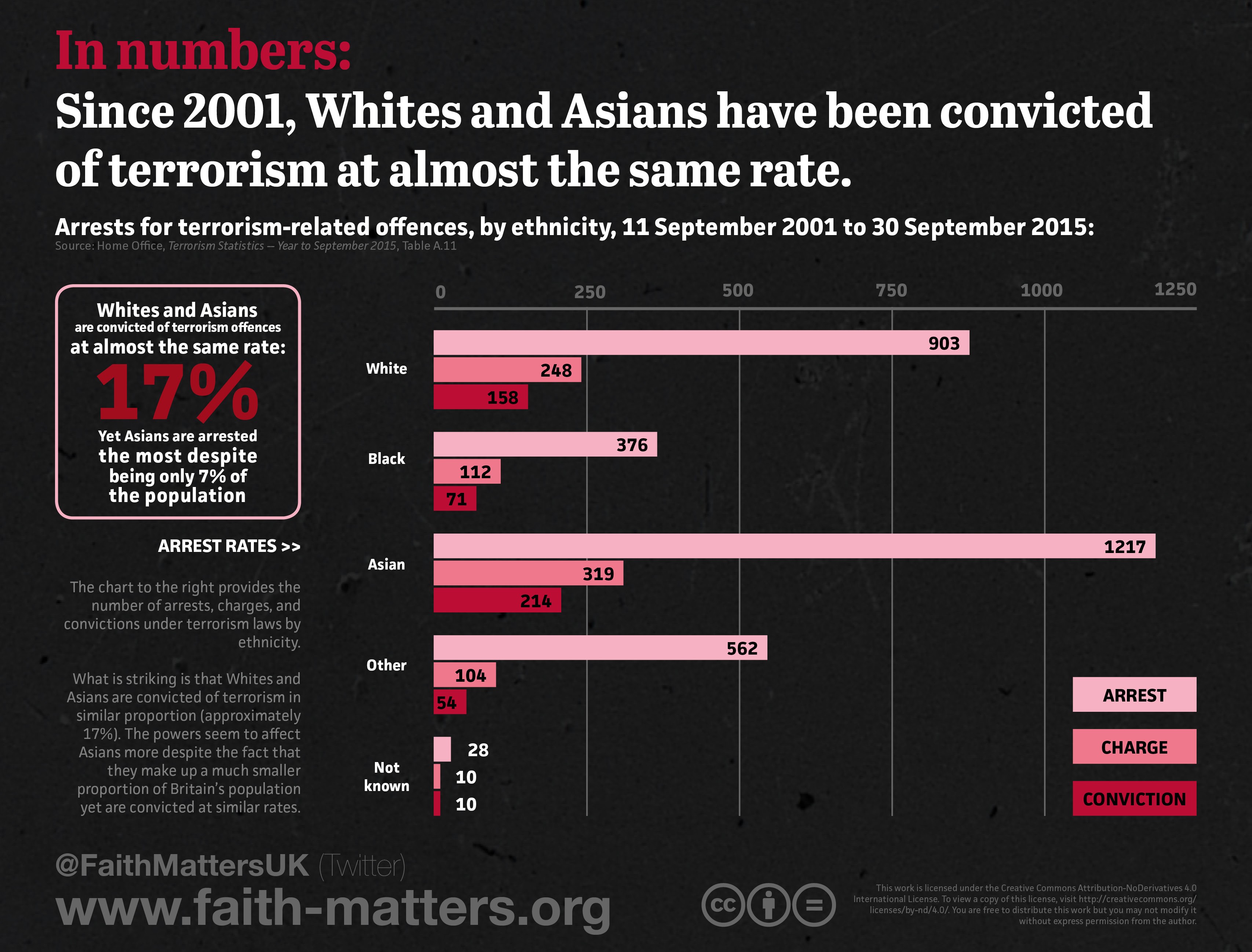

Whites and Asians are convicted of terrorism at almost the same rate from 2001 to 2015. Where there are far more Asians arrested than Whites under terrorism powers despite being a much smaller proportion of the population, the conviction rate for terrorist offences are virtually the same for Asians and Whites. This suggests that they offend at the same rate and racial profiling against Asians is ineffective in countering terrorist activity.

Methodology

In order to ascertain that Whites and Asians are convicted at a rate of 17 per cent, we divided the number of convictions by the number of total arrests for each ethnic group. This provides us with a conviction rate.

Panel 3

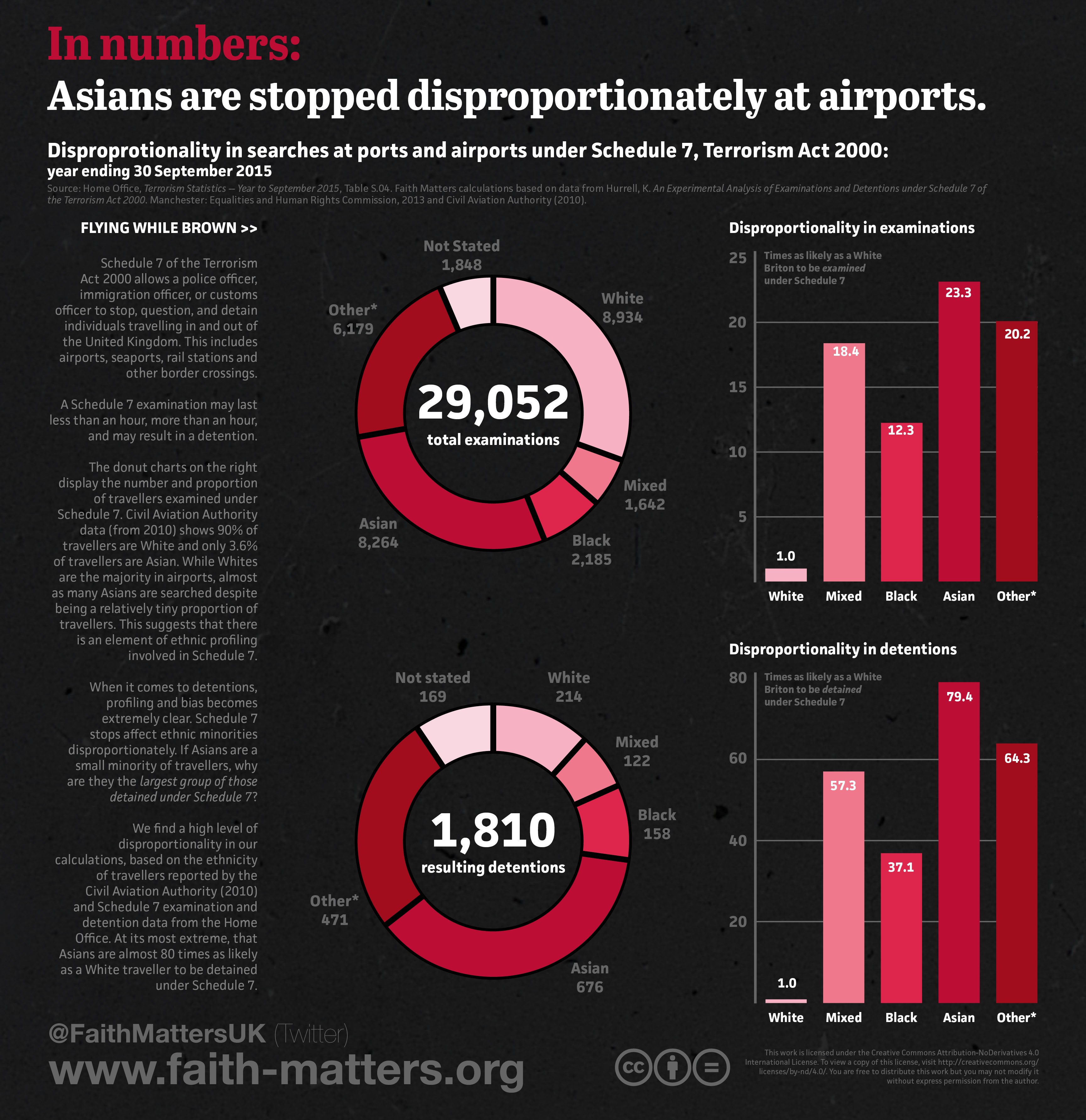

Anecdotal evidence makes abundantly clear that Asians are profiled at airports. What is surprising is that almost all ethnic minorities are at least twelve times more likely to be searched at a port or airport in the United Kingdom. Non-whites are at least 37 times as likely as a White person to be detained at a port or airport. Asians are almost 80 times as likely as a White person to be detained at an airport or port. This is a significant level of profiling that demands urgent action to ensure that British citizens and non-UK nationals visiting Britain are treated equally rather than profiled because of their ethnicity.

Methodology

In order to determine the level of disproportionality in Schedule 7 stops, we took the ratio of each ethnic group as a proportion of all those that were searched or detained. We then took the ratio of each ethnic group as a proportion of all travelers in UK airports (provided by the Civil Aviation Authority in 2010, available in an EHRC report which uses the same method as we deploy here). It is possible that these numbers have changed slightly since 2010 but we were unable to obtain free data on this from the Civil Aviation Authority (CAA) in time. Please note that the CAA provides estimates, not absolute figures on the proportion of each ethnic group as its members pass through airports. As in Panel 1, these ratios (ethnic group to search/detention, and ethnic group to the population of travelers) are compared, the product of which is then used to examine whether or not ethnic minorities are more likely than Whites to be searched or detained under Schedule 7 powers. The numbers that we found are disturbing. While there may be some margin of error based on the changing patterns of ethnicity in airports, it does provide weight to the anecdotal evidence provided by so many people who have been stopped, searched, and even detained when trying to ‘fly while brown’.

Panel 4

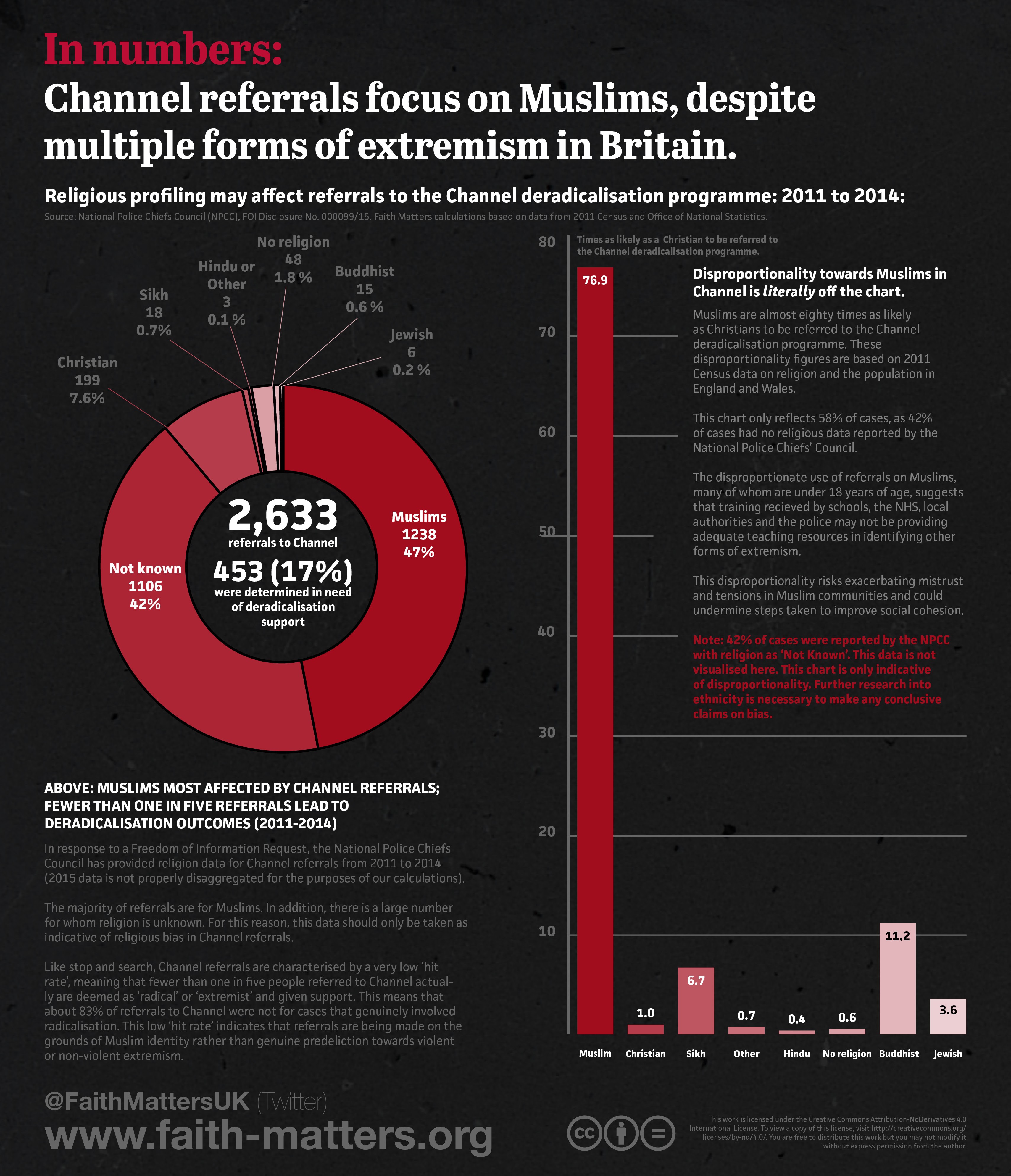

In our final panel, we examine the disproportionality of Channel referrals. We find that Muslims are more likely than any other group by an overwhelming proportion to be referred to the programme. Fewer than one in five of these referrals actually lead to the provision of deradicalisation services. This suggests that those responsible for making referrals to Channel are hypersensitive to Muslim differences and unable to accurately detect when a deradicalisation referral is actually appropriate.

It is worth noting that Sikhs, Jews, and Buddhists are also more likely than Christians to be referred to Channel as a proportion of the population (though these numbers are rather small and may not be statistically significant, representing anomalies rather than patterns) it is important to note that Hindus and Atheists are less likely than Christians to be referred to Channel.

Methodology

This is calculated using the same method as Panel 1 and Panel 3. The ratio of Muslims and each other religious group referred to Channel as a proportion of total referrals is calculated, then compared with each religious group as a proportion of the population in England and Wales per the 2011 census. We then used Christian as a reference point to ascertain whether non-Christian groups are being disproportionately affected by Channel.

The reader should note that these numbers are provisional. The information is collected from a Freedom of Information Response and there is a significant proportion of referrals where the religion of the individual is unknown. This could reduce the disproportionality observed towards Muslim but not enough to bring it anywhere close to the other religions. Given that there are more Muslims referred to the programme than any other religion combined and ‘unknown’ or ‘not stated’ religious categories, it is certain that Muslims will remain the single highest religious category even after controlling for these problems – and as better data becomes available.